Inside the Income Gap for some Black Virginians

Arguably, the most persistent demographic trend through the centuries in Virginia and the U.S. has been the difference in socioeconomic status between Black Americans and non-Black Americans. By many measures the socioeconomic gap between Black Americans and non-Black Americans has not changed considerably in half a century, adding fuel to assertions that many of our social institutions are structurally racist and disproportionately exclude Black Americans.

While an income gap exists between the incomes of Black Virginians and other Virginians, for some Black Virginians, the income gap is much smaller or almost non-existent. Exploring why this difference in income exists among Black Virginians can help us to understand at least one dimension of why Black Virginians typically earn less than other Virginians.

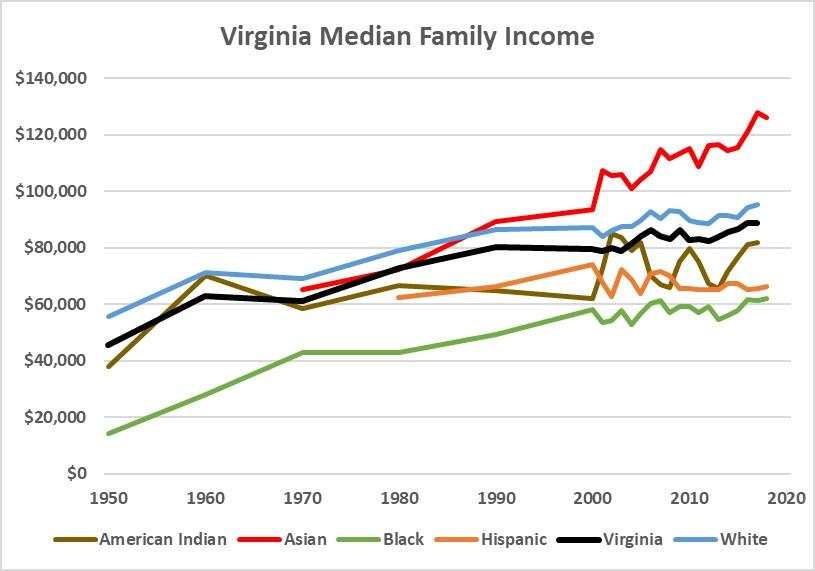

Since 1970, the income gap between Black and non-Black Virginians has not grown considerably smaller or larger.

Though it has moved down in recessions and up during economic expansions, the median family income for Black Virginians has hovered around 70 percent of Virginia’s total median family income for the last 50 years. The fact that the income gap for Black Virginians has not changed considerably since 1970 is particularly notable because the intention of the Civil Rights Era reforms and the Great Society programs that have existed since the late 1960s are in large part to help close the income gap.

By some measures, the socioeconomic gap between Black Virginians and other Virginians has grown larger over the past half century. The homeownership rate was lower for Black Virginians in 2018 than in 2000 and lower in 2000 than in 1980. Since 1940, the homeownership rate for Black Virginians has risen by only 5 percent, compared to 20 percent for all other Virginians. In a third of Virginia counties, the homeownership rate for Black Virginians is lower today than it was in 1940, including some of its largest counties, such as Chesterfield and Fairfax. As homeownership is a central indicator of the capacity to accumulate assets, this decline in homeownership among Black Virginians is a concerning trend.

Family structure may partially but not entirely explain why the income gap between Black and non-Black Virginians has not grown smaller since 1970.

The median income for Black Virginia families with two spouses present is less than 85 percent that of all Virginia families with two spouses present, but single parenting earners face steeper challenges. Single parenthood can dampen earning potential, introduce real costs in the form of childcare, and limit flexibility to pursue advanced education or work demanding unreliable hours. Between 1970 and 2018, the share of Black Virginia families led by a single parent rose from 29 to 47 percent, compared to from 12 to 19 percent for other Virginia families.

The income gap is considerably smaller for Black immigrant families in Virginia than U.S. born Black families.

Among the 10 percent of Black Virginians who are immigrants, the median family income is 11 percent lower than Virginia’s median family income. The fact that Black immigrants typically earn more than native-born Black families is unusual. Among other racial/ethnic groups, immigrants typically earn less than those born in the U.S., in part because immigrants on average have lower levels of formal education. For example, the median household income for Hispanic immigrant families in Virginia is nearly as low as native Black Virginia families, but the median income for U.S. born Hispanic families is only 10 percent lower than Virginia’s median family income, in part because second generation Hispanics have higher educational attainment rates than their parents and as a result earn more. Similarly, Black immigrants in Virginia on average have educational attainment levels closer to Virginia as a whole than U.S born Black Virginians.

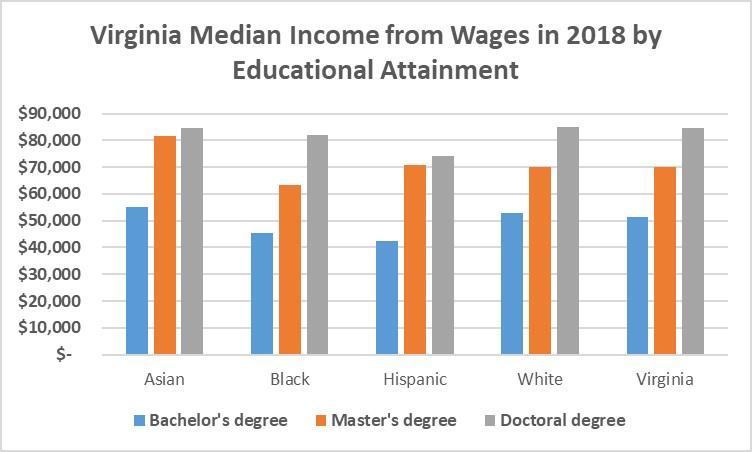

For Black Virginians with a college degree, the income gap is the smallest but still remains.

The median income from wages for Black Virginians with a bachelor’s degree is 90 percent that of all Virginians with a bachelor’s degree. Among Black Virginians with a masters or doctoral degree, the income gap is even smaller. While there is no single reason why Black Virginians with a bachelor’s degree still earn less than other Virginians with a bachelor’s degree, one reason may be that less preparation for college causes Black college students to be underrepresented in the more competitive college majors that typically lead to higher paying jobs. In context, Asian Americans are overrepresented in higher paying fields, particularly STEM, which in turn causes them to earn more on average than other Americans with the same educational attainment. It is worth noting that Black Virginians who are immigrants also earn more than other Virginians with the same educational attainment, likely for similar reasons.

The fact that most of the income gap disappears when Black Virginians and other Virginians have the same level educational attainment helps us understand why the income gap has been so persistent. Even though the share of Black Virginians who are attending college has grown considerably in recent decades, the steady increase in the wage premium paid to college graduates has pushed up the share of all Virginians attending college. Since 1970, the share of Black Virginians between ages 25 and 35 with at least a bachelor’s degree rose from 2 percent to 13 percent in 1990 to 28 percent in 2018. Yet, the share of all Virginians between 25 and 35 with at least a bachelor’s also rose from 7 percent in 1970 to 27 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2018. As a result, the gap in educational attainment between Black Virginians and other Virginian has not grown any smaller in the past three decades.

By a cruel irony, just as many institutional restraints that helped maintain the income gap in Virginia decreased in the late 1960s, wages became increasingly based on education to which Black Virginians historically had less access. Given that parents’ and grandparents’ educational attainment is one of the best determinants of their children and grandchildren’s educational attainment, Virginia’s education and income gaps may take a long time to close. Yet it is worth remembering that just between 1950 and 1970, Virginia’s income gap shrunk by third, despite Jim Crow Era barriers remaining in place during much of the period.