Extended Families: Weapon against Child Poverty?

Children living in married parent families are less likely to live in or near poverty than children in unmarried (either single– or cohabiting) parent families. Some policy advocacy groups use this to argue that marriage is the “greatest weapon against child poverty” because of the additional economic and human capital marriage adds to a household, even though there is no clear agreement about the precise ways in which parent marital status and childhood poverty interact. In fact, critics of the marriage-as-remedy position argue that economic risk may play a part in both child poverty and in the reluctance of parents to marry. As a result, they argue that economic – not relational – measures are the keys to reducing poverty.

However, this concentrated focus on parent relationship status overlooks another form of family structure pertinent to the well-being of poor children: the residential extended family. These structures may allow families to pool economic and human resources to care for children and ameliorate the effects of tough economic circumstances. In 2011, one in ten Virginia children lived in a residential extended family.

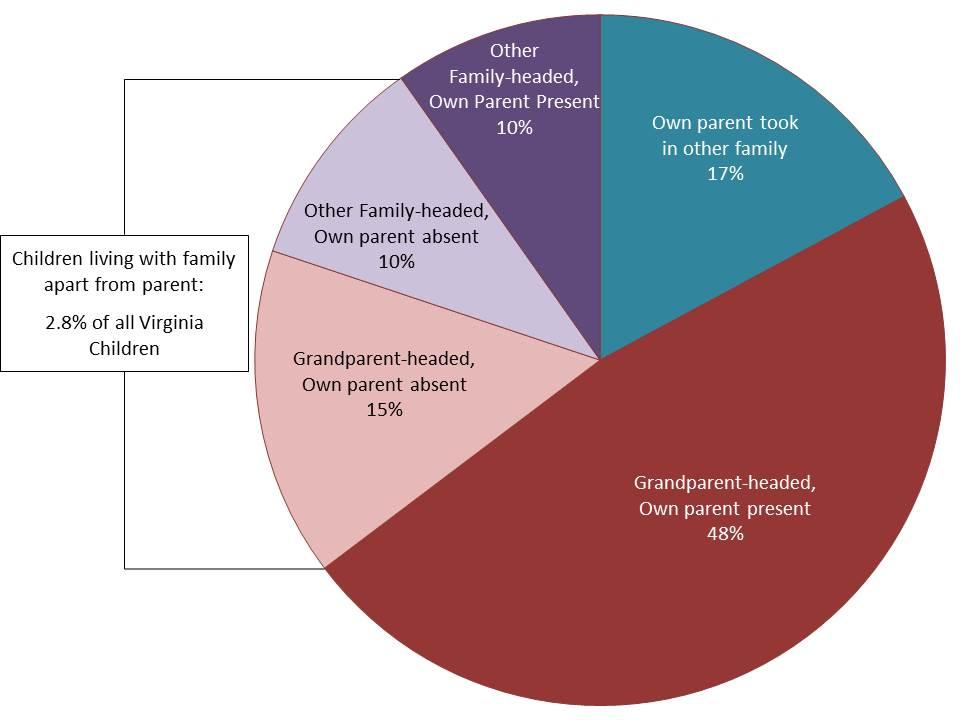

The residential extended family can take many forms, but is most common when children and their parents reside in a home belonging to one or more grandparents. Other forms include a niece (or nephew) living with an aunt and uncle, or a grandchild living with grandparents without his parents. Three-quarters of children living in residential extended families live their parents in addition to other family members. For about one in five of these children, their own parents are householders who took in another family with children.

Extended family living arrangements are relatively temporary, with roughly half ending within a year of their formation. They often form after some sort of major life event such as job loss, illness, absence of a primary parent, or the dissolution of the parents’ marriage or cohabiting relationship. By banding together, the members of extended families pool economic resources, which may help to keep them above poverty. Furthermore, combined human resources can reduce other costs. For example, when grandma and grandpa watch minor grandchildren, it not only frees other members of the household to work but also eliminates the need for paid childcare. In these ways, extended families can act as a buffer against poverty.

However, extended families can also exacerbate poverty. When the formation of extended families simply spreads already limited resources over more people – rather than pooling resources from additional income sources – it can result in greater economic distress for all members of the family, including children.

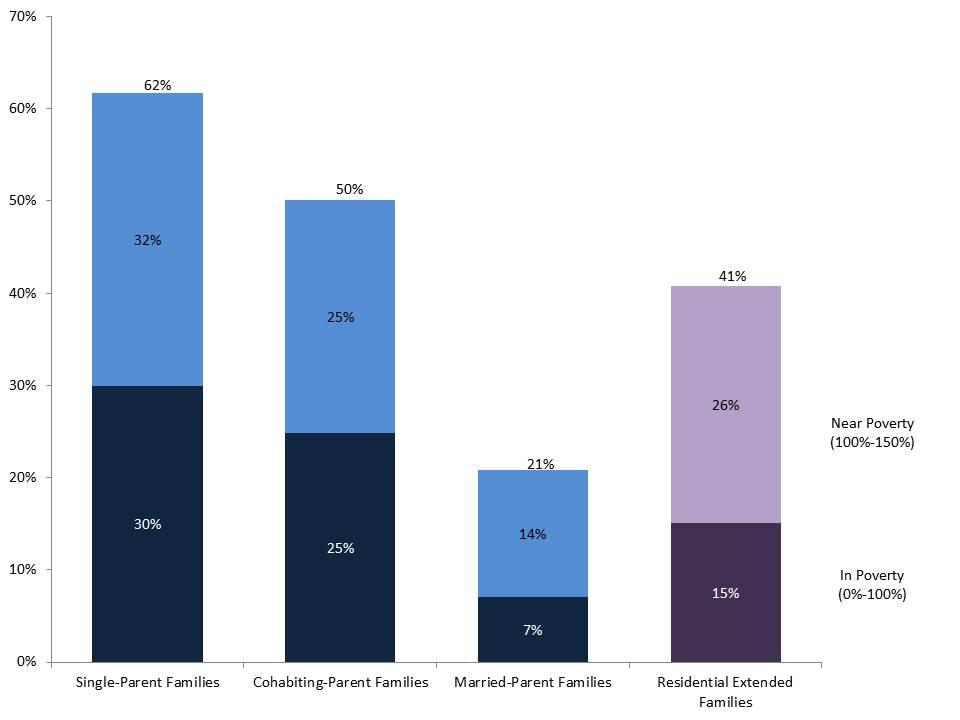

By using the Virginia Poverty Measure we see that two out of five Virginia children living in an extended family live in or near poverty. When compared to other family structures, children living in extended families are less likely to live in or near poverty than children living in households headed by single or cohabiting parents. However, they are considerably more likely to live in or near poverty than children living in homes headed by their married parents.[1]

This data provides a snap shot of one point in time, and thus cannot lead to claims about how family structure may or may not cause or alleviate poverty. We cannot argue, for example, that if single or cohabiting parents would only move in with their own parents – thus forming an extended residential family – their children would be less likely to experience poverty.

However, since residential extended families are typically formed in response to economic or relational distress, the higher rate of poverty for these children (when compared to children in married parent homes) may point to the limits of adding adults to a household as a way of ameliorating childhood poverty. While forming extended families undoubtedly improved the economic conditions of some children, two out of five children in extended residential families live in households that struggle to make ends meet.

In light of this, policy makers, political pundits, and researchers should be aware of the ways which increasing the size of families can assist kids, but also recognize the limitations of relying on relational ties to solve the problem of childhood poverty.

[1] Married-parent families include families with step parents. This category is not limited to families where the child’s two parents are married to each other.