Driving alone: how Virginians get to work

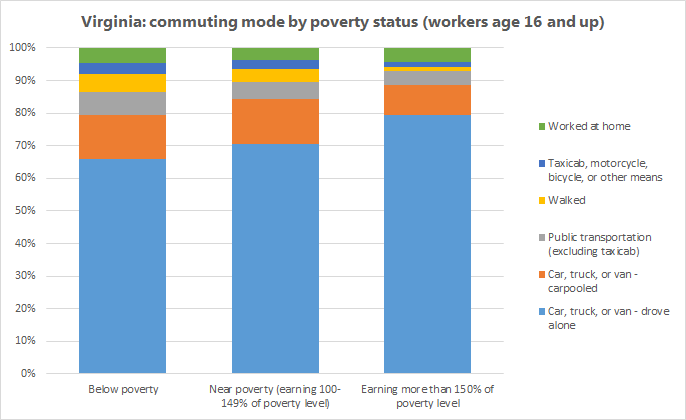

The newly released 2010-2014 ACS 5-year estimate data includes information on how people get to work. Like most other Americans, Virginians across all age and income groups are overwhelmingly likely to get to work by driving a motor vehicle alone. Workers living below poverty level are slightly more likely to take other modes of transportation, as are younger workers.

Where do the fewest workers drive alone to work?

Because university students tend to use alternative transportation more than other groups of people, Virginia’s college towns dominate the list of places where the fewest people commute by car. Overall, Lexington has the highest percentage of residents who say they walk to work – but those are overwhelmingly undergraduate students. I was interested in looking at how people of prime working age – 25 to 64 years old – commute to work. I also wanted to take out people working at home since, strictly speaking, they’re not commuting at all.

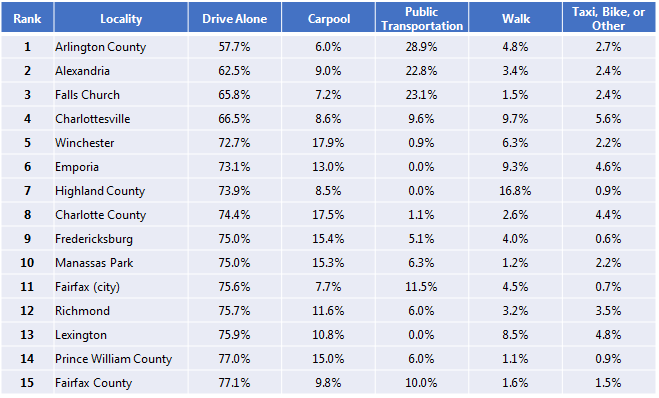

With those groups taken out, here are the localities where the lowest percentage of workers get to work by driving alone in a motor vehicle:

There are a number of factors influencing mode share. The most obvious ones are population density and access to transit. Unsurprisingly, the list is topped by the dense Northern Virginia localities with access to the Washington, DC Metro system. Outside of WMATA, Charlottesville and Richmond also have reasonably well-used transit systems.

Another factor is the concentration of employment. Research suggests that job density is a greater factor in predicting alternative transportation use than housing density. If it’s difficult or costly to drive to and park at work, workers will be more likely to catch a ride than if they simply live in an urban neighborhood and commute elsewhere. Winchester, Fredericksburg, and Prince William County don’t have much in the way of public transit, but they do have a large number of residents working a long way away in dense Washington, DC. As a result, they have high percentages of workers carpooling over that distance.

More important than many people realize is how far away employment destinations are. A large metro area may have be dense, but its workers are also likely to be traveling long distances across the area. Smaller towns that are not satellites for a larger metro are likely to have more people walking. Charlottesville’s small size makes walking and biking attractive, since most workers aren’t commuting very far (Charlottesville also boasts some of the shortest commute times). Similarly, sparsely populated Highland County may seem out of place on this list. Its small sample size does mean large margins of error, but even accounting for those margins, a significant proportion of the county’s roughly 950 workers report that they primarily walk to work. This makes sense given the county’s extreme isolation and the fact that a sizeable chunk of those workers are living and working in older and very compact hamlets like Monterey, a tight cluster of houses and businesses that you can walk across in about 10 minutes.

The last thing to watch is the income level of the locality. In addition to being a smaller town with shorter commutes, Emporia (which comes in at number 6 on this list) has a significantly lower median income than the state. Several other counties with low median incomes or high poverty levels are higher on the list than their density and transit access would suggest.

Look for yourself

I’ve put the commuting data, broken down by age and mode, into a tableau graphic that you can use below. Pick which localities you want to compare and the age groups and modes you want to include: