Out-migration from Virginia continues for the fifth consecutive year, pushing population growth below national levels

This morning the Weldon Cooper Center at the University of Virginia released its 2018 population estimates for Virginia’s counties and cities. The estimates show that Virginia’s total population has continued to grow, passing 8.5 million in 2018. Though Virginia added over 50,000 new residents in the past year, growth is noticeably slower than ten years ago when Virginia’s population was increasing by closer to 100,000 annually. Over the past five years, Virginia’s population grew by 3.2 percent, which is slightly less than overall growth of the U.S. population at 3.5 percent.

One of the key reasons for Virginia’s slower population growth is that there are more Virginians moving out of the Commonwealth than there are residents from other states moving in. Instead of gaining 10 to 20 thousand residents each year from other states, Virginia has been losing 10 to 20 thousand residents to other states.

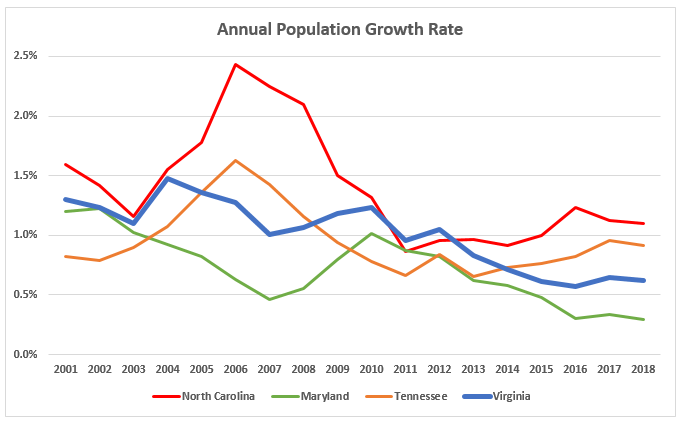

Because the shift to out-migration in Virginia began in 2012-2013, about the same time as the federal budget sequestration, the contraction in federal spending is the most obvious reason for more Virginian’s moving out. In Maryland, population growth also decelerated after 2012. As more Virginians and Marylanders have been moving south, population growth has picked up in North Carolina and Tennessee. Though the federal budget is the primary culprit for Virginia’s shift to out-migration, the mid-2000s economic expansion and the late 1990s dot com boom also slowed growth in Virginia and Maryland as more residents moved south.

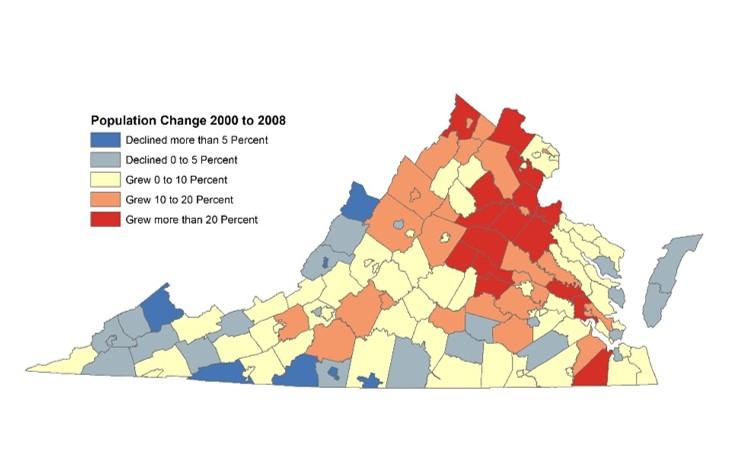

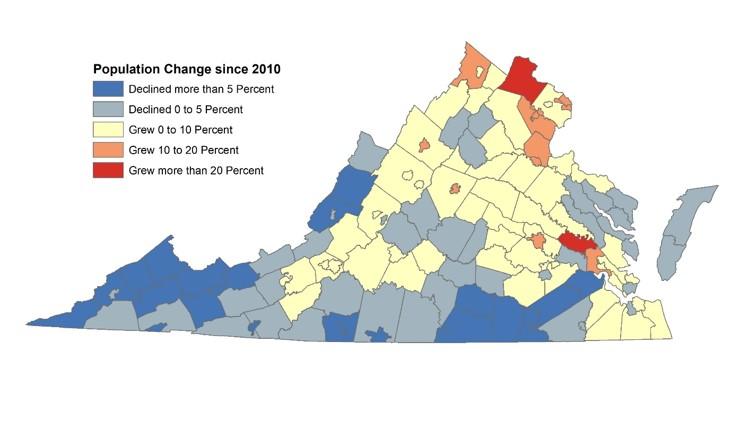

Within Virginia, a disproportionate share of growth has been concentrated in Northern Virginia this decade, particularly compared with past decades. Last year, Northern Virginia accounted for sixty-seven percent of Virginia’s total population growth, helping push the region’s population past three million in 2018. Northern Virginia’s population is now larger than the combined population of the Richmond and Hampton Roads metro areas

Outside of Northern Virginia, a number of suburban counties, including New Kent and Frederick, and many of Virginia’s independent cities have experienced the fastest population growth this decade. Ten of the twenty fastest growing Virginia localities since 2010 have been independent cities. Roanoke City’s population count is now greater than 100,000 for the first time since 1983, and Richmond’s population growth has outpaced neighboring counties.

With slower statewide population growth has also come more population decline on the local level. Since 2010, over half of Virginia’s counties have lost population with much of the decline concentrated in rural and non-metro counties. Every Virginia county bordering North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky has lost population this decade.

While the geographic distribution of population loss in the Commonwealth may not be surprising to many Virginians, it is important to note that the cause of population decline varies from county to county. In about one third of Virginia, including much of the Coalfields and parts of Southside, counties are losing population from residents moving out and an aging population (there are more deaths than births). In another third of Virginia, primarily counties on the edges of metro areas, the population is declining or growing very slowly because whatever gains in population they receive from people moving in is cancelled out by having more deaths than births.

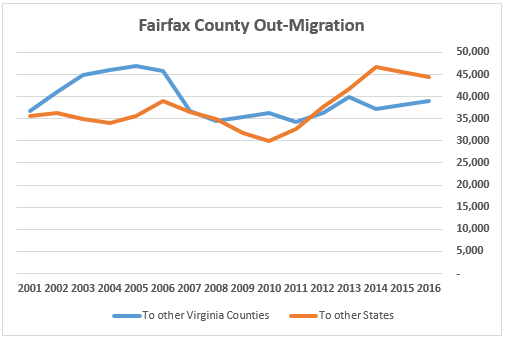

Perhaps no county can explain why most of Virginia is declining in population better than Fairfax, where one in seven Virginians live. A disproportionate share of young Virginians, particularly those who have graduated college, move to Fairfax for their first jobs. After they have become more established in their careers and often after starting a family, many Fairfax County residents begin moving out farther into Northern Virginia’s suburbs, while a large number move out of Northern Virginia altogether. As a result of out-migration (since 2010), Fairfax County has lost 18,000 residents, but still manage to grow because it had 82,000 more births than deaths.

Migration data shows that most Virginia counties grew during the 2000s in part from Fairfax County and other Northern Virginia residents relocating to them. However, during the last recession, out-migration from Fairfax County to other Virginia counties slowed and even as the economy has recovered, this remains the case as more Fairfax County residents are moving out of state rather than to other Virginia counties. As a result, population and school enrollment growth has slowed or slipped into decline in Virginia counties that had, in the past, attracted Fairfax residents.

If Virginia’s current population growth rate continues for the remainder of the decade, Virginia will have grown by 7.8 percent, down from 13 percent in the 2000s and the lowest growth rate since the 1920s. While this is a large drop in growth, it shouldn’t be a complete surprise. At the beginning of the decade, Virginia’s population growth was projected to decelerate to about 10 percent in the 2010s and to well below 10 percent in the 2020s as the Commonwealth’s population ages and the number of deaths rise. A drop in births, out-migration and more deaths than expected all contributed to an earlier-than-expected slowdown in growth. In the next decade, Virginia’s population growth will likely increase as out-migration lessens, but the higher growth rates experienced in past decades will not likely return due to Virginia’s aging population.