Can Virginia’s cities keep growing?

Perhaps the most surprising demographic trend over the past decade in Virginia—and much of the U.S.—has been the resurgence of growth in cities after nearly half a century of population decline or stagnation. In the early 2000s, after the population of Virginia’s independent cities hit their lowest point since the 1950 census, many of Virginia’s cities began growing again. Local zoning reforms, changing property development models, and a renewed public interest in urban centers all helped fuel the recent growth. Yet the recent population growth trend in Virginia’s cities may be more fragile than it appears; Virginia’s cities experienced their most rapid growth during the last recession when the economy and strict mortgage regulations made it difficult to buy a home. Now that the economy and housing markets are the strongest they have been in over a decade, migration out of many of Virginia’s cities is rising.

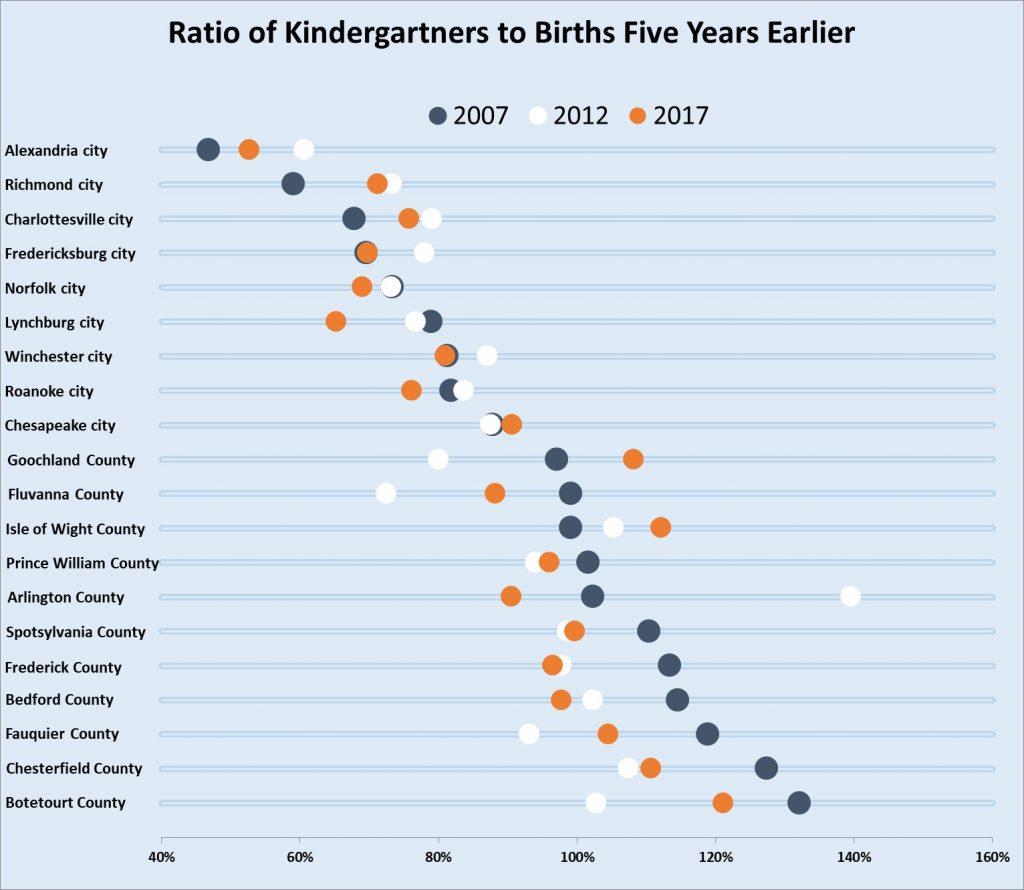

One of the primary drivers of the recent population growth in Virginia’s cities has been families with children. Before the recession, families with children often moved out to suburban counties for more space and newer housing. As a result, in city school divisions, such as Alexandria and Charlottesville, fewer than 60 percent of children born in the cities enrolled in Kindergarten in some years. However, once the recession hit, families found it more difficult to purchase a home, so many rented in cities (where a larger share of the housing stock is rental homes), which caused the share of children staying in some Virginia cities to rise by 20 percent.

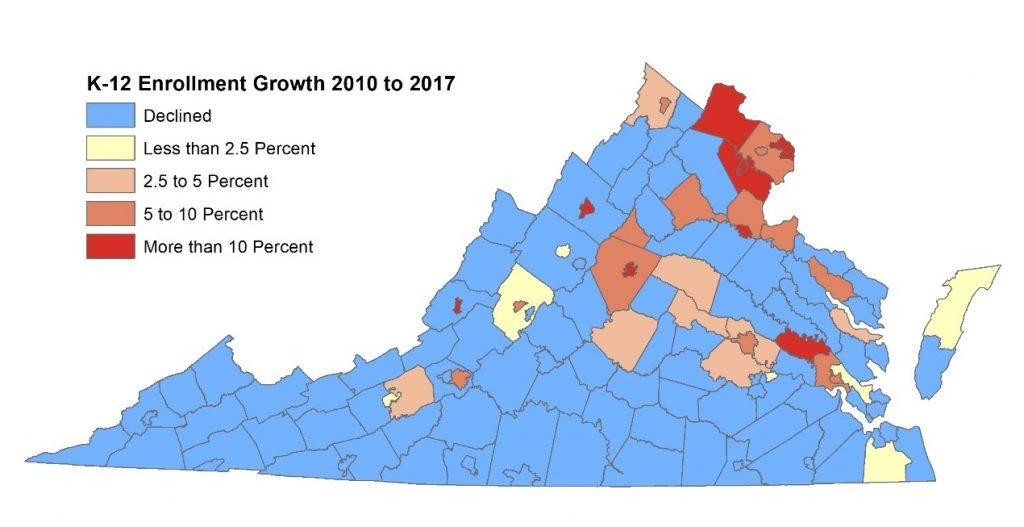

The net effect of more families staying in cities has not only been an increase in population, but also in public school enrollment. So far this decade, independent cities—and predominantly urban Arlington County—have accounted for seven of the ten fastest growing Virginia school divisions. Meanwhile, in most of Virginia’s suburban counties, school enrollment and population growth have both slowed considerably, and in many cases, have shifted to decline.

Over the last couple years, the share of children born in Virginia cities that later enroll in city schools has fallen, indicating an increase in families moving out. And while more families are still choosing to remain in Virginia cities than before the recession, population growth in Virginia’s cities has slowed. At the same time, suburban counties, such as Fauquier and Fluvanna, are attracting more families with children but still fewer than before the recession.

A return to the decades of declining population or stagnant growth is unlikely, however. Virginia’s cities remain attractive to other types of households, such as young adults who are increasingly delaying marriage and homeownership. By 2030, Virginia’s population over age 65 is expected to be nearly double its 2010 size, which might mean a good deal more retirees looking to downsize.

After the recession, many cities’ populations surged while home construction remained well below pre-recession levels. As a result, home vacancy rates have fallen noticeably in Virginia cities, particularly when compared with Virginia counties. Home prices have also risen faster in many Virginia cities. Prior to the recession, owner occupied housing in both Charlottesville and Richmond was 27 percent cheaper than in surrounding counties. By 2016, housing was only 12 percent cheaper in Charlottesville and 8 percent cheaper in Richmond.

In the coming years, home construction levels will need to increase for Virginia cities to continue growing at recent rates. Some cities, such as Richmond, have seen more home construction. But building new homes in cities can be difficult; most development in cities is infill which often requires more paperwork and faces more public opposition than greenfield developments.

If cities are not able to supply enough housing to meet demand, the recent trend of falling vacancy rates and rising home prices will likely continue, along with slower population growth. While a stronger property market and more tax revenue, without the nuisances caused by population growth, may appear to be a win-win situation, it does have its costs. The recent shift to more families leaving Virginia cities for nearby suburban counties may be one downside. An increasing number of residents being priced out of their neighborhoods could be another. Compared to the trends that most Virginia cities experienced in the decades after 1950, their current difficulties managing growth are a good problem to have.