Red State, Blue State: Voting in Context

We released a report today on demographic change in Virginia and what it means for presidential election outcomes in the state. One takeaway from the study – of surprise to no one who follows elections closely – is that the impact of demographic changes on presidential elections in the state have been muted by differential turnout rates among demographic groups. For instance, minority voters, a growing population that has favored Democratic presidential candidates in recent elections, have lower turnout rates than do white voters.

Lots of things influence turnout. A study on demographic change will, reasonably enough, emphasize demographic factors. But the decision to show up at the polls on Election Day isn’t simply a function of individual attributes. People who vote (or don’t) are not simply better (or worse) citizens.

They vote, as well, because their neighbors or co-workers vote; because a campaign asked them to vote; because they believe to some degree that politicians care what people like them think. They don’t vote because they moved in the past year and are no longer properly registered; because they don’t have the time to vote between childcare, commuting to work and work itself; because they are ill or disabled; and because they don’t like their choices or don’t think the outcome will change anything of relevance to their lives.

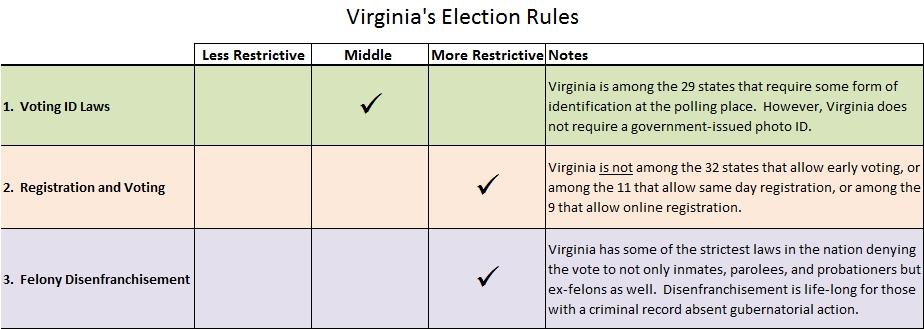

Finally, individuals respond to deliberate policy choices, such as: state voter ID laws; new regulations of voter registration and restrictions on early voting; and ex-felon disenfranchisement laws.

These policies vary across the states, and their impact varies across the population.

1. Voter ID laws:

Voter ID laws have been in the news a great deal recently, as some states have enacted new requirements that voters provide ID at the polls (Kansas, Rhode Island, Wisconsin) or strengthened existing laws by limiting acceptable identification to photo IDs (Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas).

Voter ID laws, particularly those requiring photo ID, have been the subject of much debate precisely because they are expected to impact the population differently, based on demographic characteristics. Several studies have estimated that somewhere between 6 and 11 percent of voting-age citizens lack a valid photo ID, and the percent is higher among blacks, the elderly, and low-income citizens. Some states have passed photo ID bills that expressly exclude photo IDs issued by higher education institutions in the state, which would clearly impact college-age citizens disproportionately. Additional research estimates that strict voter ID laws reduce turnout by about 2 percent – a small reduction that could alter the outcome in a close contest.

Virginia already requires voters to present a form of identification – currently, a voter registration card, a Social Security card, a valid driver’s license, an employee identification card that contains a photograph, or any other identification card issued by a state or federal agency.

In 2011, a couple of voter ID bills were introduced, but none passed. In 2012, Virginia amended the existing law to allow additional forms of identification (a valid student ID from a Virginia college or university, a copy of a current utility bill, bank statement, or government check or paycheck, or a concealed handgun permit). So, contrary to the national trend, Virginia has actually made it easier for voters to fulfill the requirement of the law. Though the same amendment also requires that if an acceptable ID cannot be shown, the voter can cast only a provisional ballot, to be counted only if the voter submits the necessary identification within three days of the election (previously, a voter without an acceptable ID could cast a ballot after signing an affidavit stating she or he was the named registered voter). None of these changes, however, can go into effect until they’ve been approved by the U.S. Department of Justice under the Voting Rights Act.

2. Registration regulations, Early voting restrictions:

The United States is one of the few democracies that place the burden of voter registration entirely on citizens themselves (the others are Bahamas, Belize, and Burundi). Several policies have been enacted recently to make the process more difficult. For instance, four states now require documentary proof of citizenship when registering to vote (before 2005, no state required this); two states have limited community-based voter registration drives (Florida, Texas); several states have sought to eliminate Election-Day registration (still pending). All of these policies are expected to disproportionately impact minority voters.

In addition, five states reduced early voting (Florida, Georgia, Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia), with legislation in additional states still pending.

The United States is one of two democracies in which a large number of people convicted of felonies are disenfranchised after completing their sentences (Belgium is the other). Iowa and Florida have been in the news because they had made sweeping changes to ease the restoration of voting rights in the recent past (2005 and 2007, respectively), but last year governors in both states reversed the reforms, returning to a policy of de facto permanent disenfranchisement (the same policy as Virginia). Nationally, about 5.85 million people are disenfranchised due to felony convictions; only a quarter of those are in prison. Nearly half are ex-felons who have completed their time in prison, probation, or parole. Nearly 8 percent of the adult African American population is disenfranchised compared to 2 percent of the non-African American population.

In short, the election rules matter. They make it systematically easier or harder for citizens to vote. Policies that erect barriers to voting generally fall harder on the segments of the population with fewer resources to overcome them, resources like information, time, money, experience navigating bureaucracy. More subtly, election rules, and their more or less restrictive nature, send clear signals to the public about the value and legitimacy of their participation in the democratic process.

You can read the full report here.