School Enrollment in a Post-Pandemic Virginia

On January 13th, the Demographics Research Group provided a presentation to the State Senate Finance & Appropriations Subcommittee for K-12 Education. In our presentation, we focused on the impact that births and private education will have on enrollment in 2020s. The following post is a summary of the trends included in that presentation.

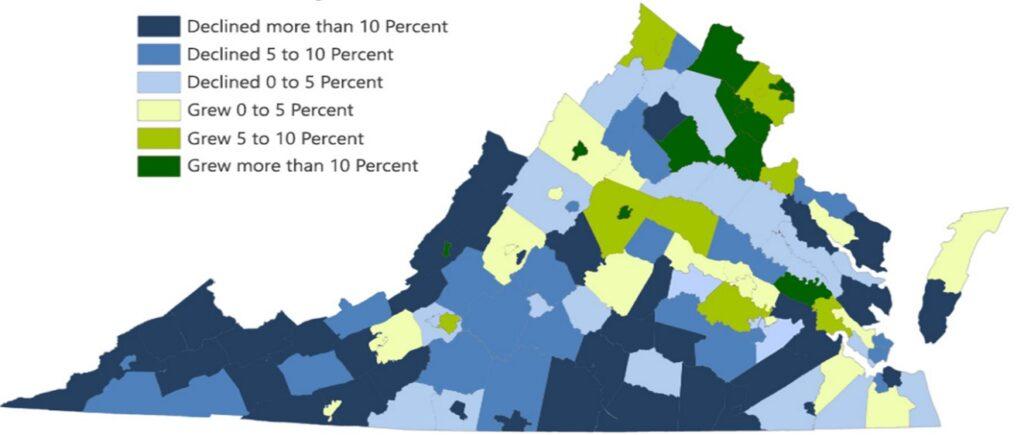

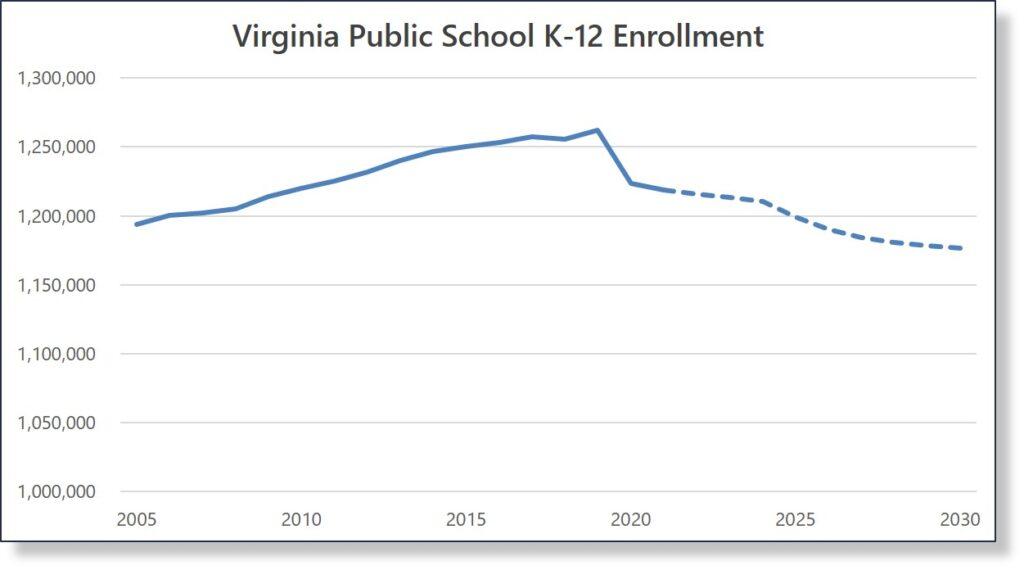

Before the pandemic began in 2020, the number of students in Virginia’s public schools had been growing steadily for decades. During the 2010s, the K-12 enrollment in Virginia public schools overall increased by 42,000 students. At the locality level, however, public school enrollment trends were much more mixed. In fact, most of Virginia’s school divisions experienced a decline in enrollment but its ten largest school divisions added more than enough students to make up for enrollment losses elsewhere in the Commonwealth. The pandemic, however, has significantly altered school enrollment trends: The gains in public school enrollment seen in the 2010s have been erased, while enrollment in homeschooling and private schools has grown substantially as many parents have opted to educate their children privately.

Source: Virginia Department of Education Fall Count

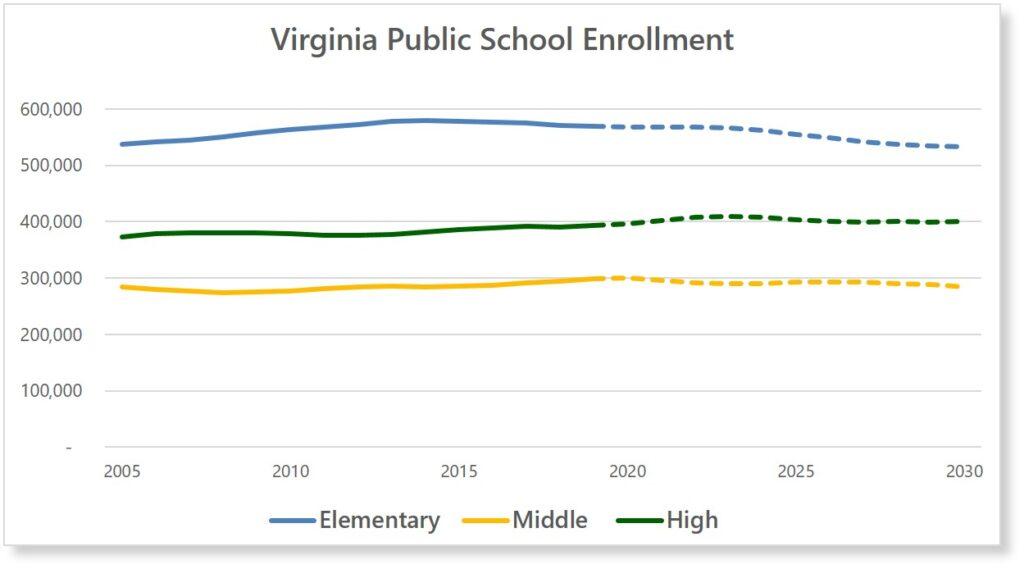

The recent decline in public school enrollment and the surge in homeschooling and private schooling have both been widely reported but what is less commonly known is that well before the pandemic began, enrollment in Virginia public schools was on track to begin declining in the early 2020s. The first indicator of school enrollment decline in Virginia was in the fall of 2013, when Virginia’s entering kindergarten class was substantially smaller than the year before. By 2015, Virginia’s total elementary school enrollment had declined after several years of increasingly smaller kindergarten classes. By this fall, even without the pandemic, Virginia’s public school enrollment was expected to enter an indefinite period of enrollment decline—with close to 50,000 fewer students by 2030.

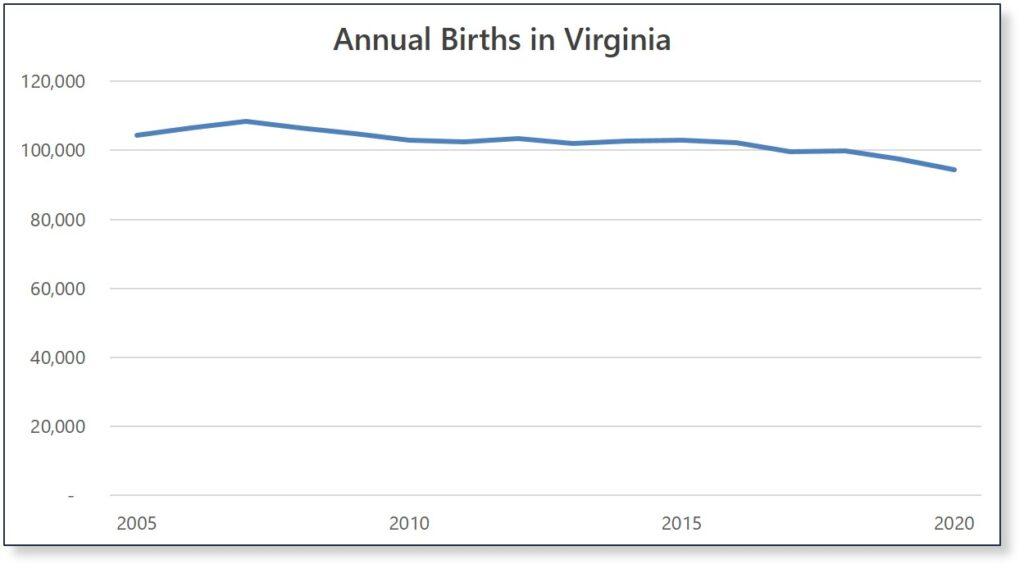

The main reason why Virginia’s public school enrollment was expected to begin shrinking this fall was that the number of births in Virginia had been declining since the late 2000s. School enrollment closely follows the birth rate: births peaked in Virginia in 2007 and began to decline, kindergarten enrollment peaked five years later in 2012 and then began to decline. In 2007, there were 108,416 births in Virginia, but by 2020 the number of annual births had steadily declined to 94,474, and the preliminary number of births in 2021 appears even lower.

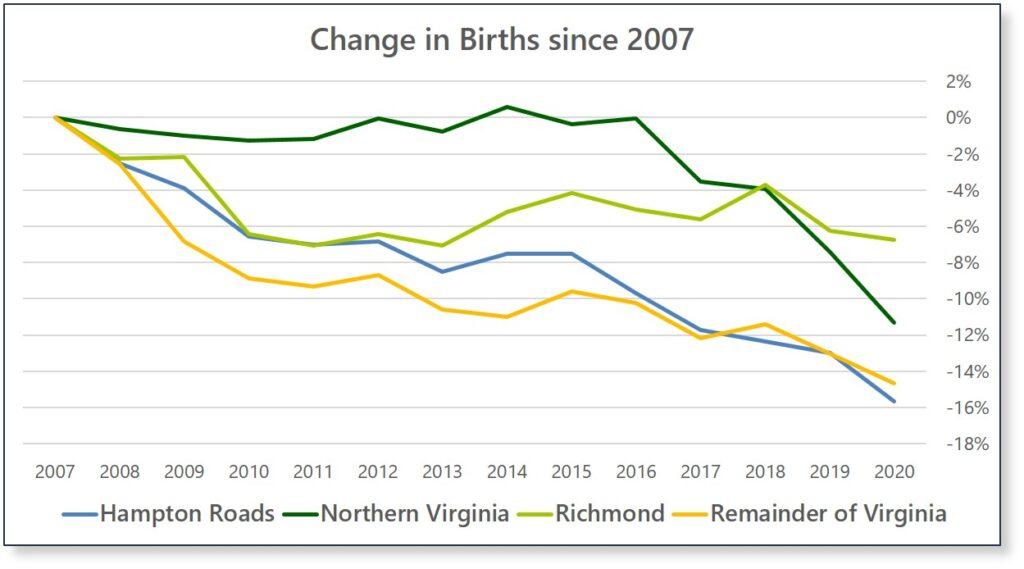

Though the number of births has fallen across Virginia’s regions, the more rural areas of Virginia typically were the first to experience a decline in births during the late 2000s. The early fall-off in births in Virginia’s rural localities is the main reason why their student enrollment declined during the 2010s, even as enrollment in Northern Virginia continued to grow. In just the last few years though, Northern Virginia has experienced a remarkable decline in births, fueled in part by young adults and families leaving the region. Between 2016 and 2020, the number of births in Northern Virginia fell from an all-time high to its lowest level since 2000, when the region’s population was a third smaller than today.

The recent decline in births in Northern Virginia is so significant that its impact on school enrollment will occur as soon as this decade. Between 2016 and 2020, the number of births in Fairfax County declined by 15 percent, and by 18 percent in Arlington County. For context, Virginia’s Coalfield counties, which have seen the largest declines in school enrollment in recent years, experienced a 17 percent decline in births during the same period. Though Northern Virginia and the Coalfields often appear on the opposite extremes of Virginia’s demographic trends, by the end of this decade, school enrollment trends in Northern Virginia may look a good deal more like those in Virginia’s Coalfields.

Even if Virginia were to enter a decades-long baby boom beginning in 2022, it would not be soon enough to reverse Virginia’s expected decline in enrollment. Births have a large impact on school enrollment but it can take over a decade to see an increase in enrollment as a result of an increase in births. Another factor affecting public school enrollment, besides births, is that tens of thousands of students left the public school system during the pandemic. So while the decline in births was expected to result in a decline of 50,000 students by 2030, the loss could be significantly larger – potentially closer to 100,000 students by 2030 if those students who left public schools during the pandemic do not return.

The impact of Virginia’s declining fertility rates is in its infancy, affecting first k-12 school enrollment, but then over time, affecting higher education and eventually the workforce. After the middle of this decade, the number of high school graduates will likely begin to decline in Virginia, resulting in a shrinking college-age population, leaving community colleges and universities to compete for fewer college-age students. Fewer births, over time, could eventually result in a smaller workforce so that employers may have to compete more aggressively to fill positions, similar to what occurred during the pandemic.

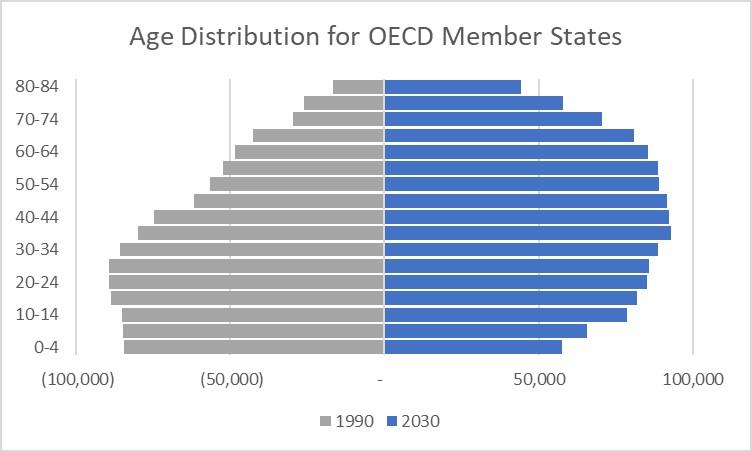

Since the 2000s, Virginia’s declining birth rates are not an anomaly but rather the norm in most developed countries. Birth rates in Virginia, the U.S. and other member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries(OECD) all declined from nearly 2.1 births per women to around 1.65 (over 20 percent below replacement levels needed to replace the population). In OECD countries, twice as many residents turned 18 than 65 in 1990 but by 2030 the United Nations projects that more residents will be turning 65 than 18. While for many the pandemic may have seemed to have turned the world upside down, declining birth rates are literally turning age structures upside down for many countries. The social and economic changes in Virginia brought on by lower birth rates will occur more gradually than those caused by the pandemic but their impact will undoubtedly be greater and longer lasting.