In the era of remote work, housing costs may slow Virginia population growth further

On July 13, 2022, the Demographics Research Group presented our analysis of the interrelationship between Virginia’s housing market and population trends to the General Assembly’s Housing Commission. After receiving a number of inquiries regarding the presentation, we are sharing a summary of the presentation with expanded commentary on some noteworthy trends.

Throughout American history, the availability and cost of housing has influenced where people move and, consequently, where the country’s population has grown. One of the most significant demographic trends in the U.S. during the 20th century was the southward shift in growth after World War II. Many northerners moved to states in the Sunbelt, drawn, in large part, by cheaper housing and a lower cost of living. Virginia was one of the southern states impacted the most by this change. In the 1920s, Virginia’s population growth rate was only 5 percent, but by the 1940s, growth had soared to 24 percent. Each decade since then, Virginia’s population has grown faster than the rest of country.

As recently as the 1990s, Virginia was, like its southern neighbors, a significantly more affordable place to live than most northeastern states. The median home price in Virginia in 1990 was half that of Connecticut but close to a third more than in North Carolina. However, over the past couple of decades, home prices in most places in Virginia rose faster than the rest of country. As a result, by 2019, Virginia’s median home price was slightly higher than the median home price in Connecticut and 50 percent higher than in North Carolina. Home prices in every Virginia county north of the James River, except Amherst, have risen faster than the rest of country. In Northern Virginia, the combination of a strong economy and relatively low home construction rates have caused home prices to increase more than any east coast metro area over the past two decades. Today, Arlington and Fairfax have the most expensive housing among all East Coast counties, after only Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

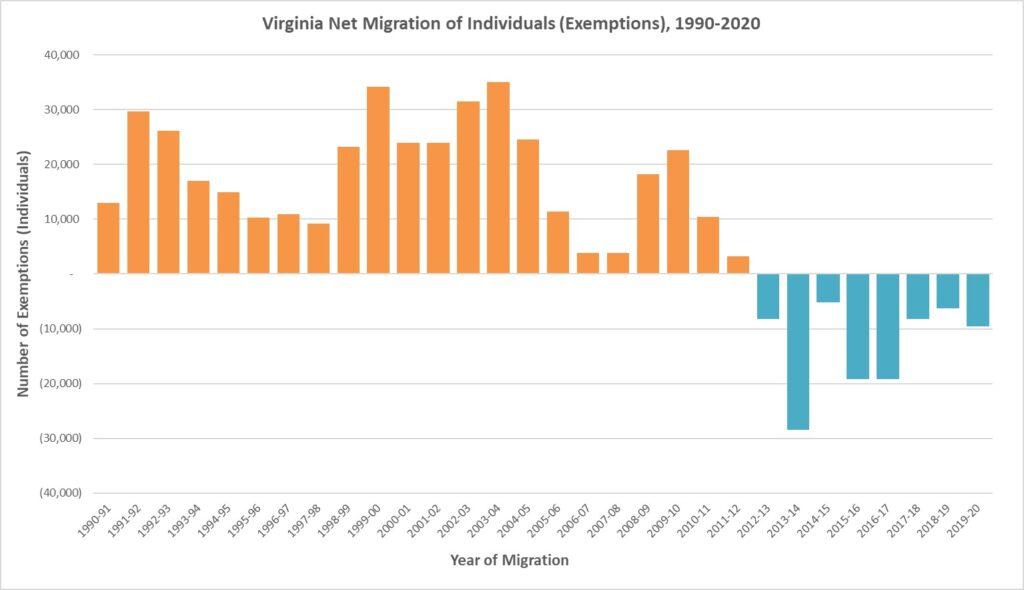

As home prices began to soar in Northern Virginia during the 1990s dot-com boom, more residents moved further out into its suburbs where there was a better supply of new, more affordable homes, helping fuel the growth of counties located on the outer edges of the metro area and beyond. By the early 2010s, the outskirts of Northern Virginia contained the largest concentration of counties in the country where over one in ten residents spent 3 hours commuting daily to work. Not coincidentally, at about the same time, IRS data began to show an increasing number of Northern Virginians leaving Virginia altogether, slowing population growth in the region and in Virginia. In 2013, so many Northern Virginians left that Virginia as a whole had more people moving out to other states than in for the first time since World War II.

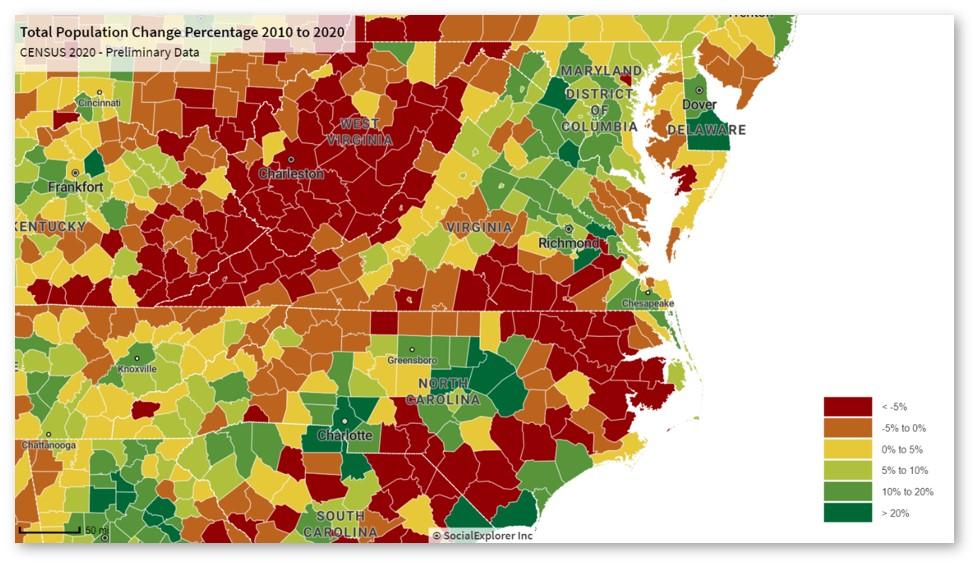

Most of those who left Northern Virginia moved south to Sunbelt metro areas where the cost of living was lower and economies were thriving. In Wake County (Raleigh), North Carolina, one of the top destinations for Northern Virginians, the median home price was half that of Fairfax County’s in 2019 but its average salary for new hires was only a third lower. Wake County’s housing prices were lower, in large part, due to its ample supply of new homes, and in 2021, more homes were built in Wake County than in all of Northern Virginia. Thirty years ago, the population of Wake County was half that of Fairfax County, but after decades of new residents moving into North Carolina’s Research Triangle—many of them from Northern Virginia—Wake County surpassed Fairfax County last year.

Because Northern Virginia has contributed to most of Virginia’s population growth since 1990, the exodus to Sunbelt metro areas has caused Virginia as a whole to experience one of the sharpest slowdowns in population growth among all states during the past decade. Even outside Northern Virginia, much of the Commonwealth’s growth—including Charlottesville, Richmond and Winchester—has, in recent decades, been driven directly or indirectly by Northern Virginia. In other parts of Virginia, particularly south of the James River and in eastern Virginia, population growth has become increasingly rare. During the 2010s, every Virginia county bordering North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky lost population.

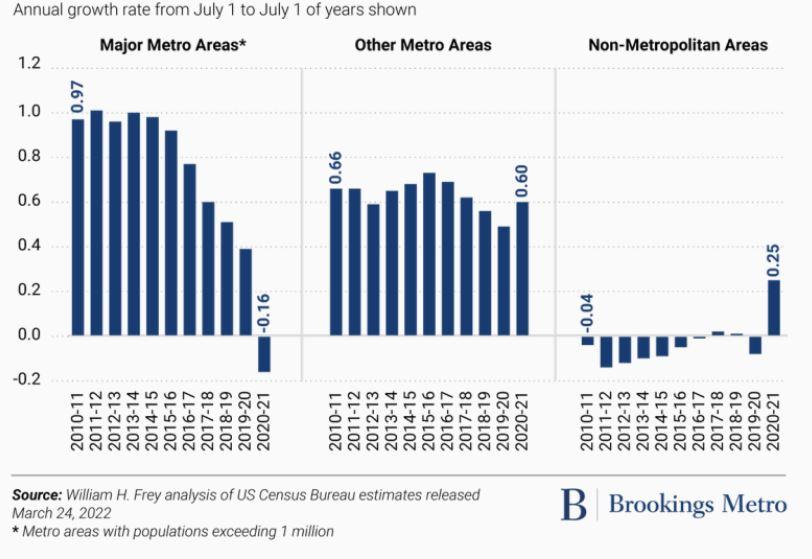

While Virginia had undoubtedly become dependent on Northern Virginia to drive its economic and population growth, it was common in many states for population growth to be concentrated in the largest metro areas during the past two decades. Large metro areas have tended to recover more quickly in recent recessions, notably after the dot-com bubble and the financial crisis, making them an attractive location for job seekers. But long periods of economic expansion, rising housing prices, and an improving economy outside metro areas typically cause residents to leave large metro areas. This trend was quite noticeable during the mid-2000s and more recently in the second half of the 2010s, as the U.S. economy slowly recovered from the Great Recession and more people moved out of large metro areas, boosting growth in smaller metros and rural areas. In 2017, the U.S. rural population grew for the first time in the decade, and each year since then, it has continued to grow. In 2021, Virginia’s rural counties built twice as many new homes than in 2016, while Northern Virginia built fewer homes.

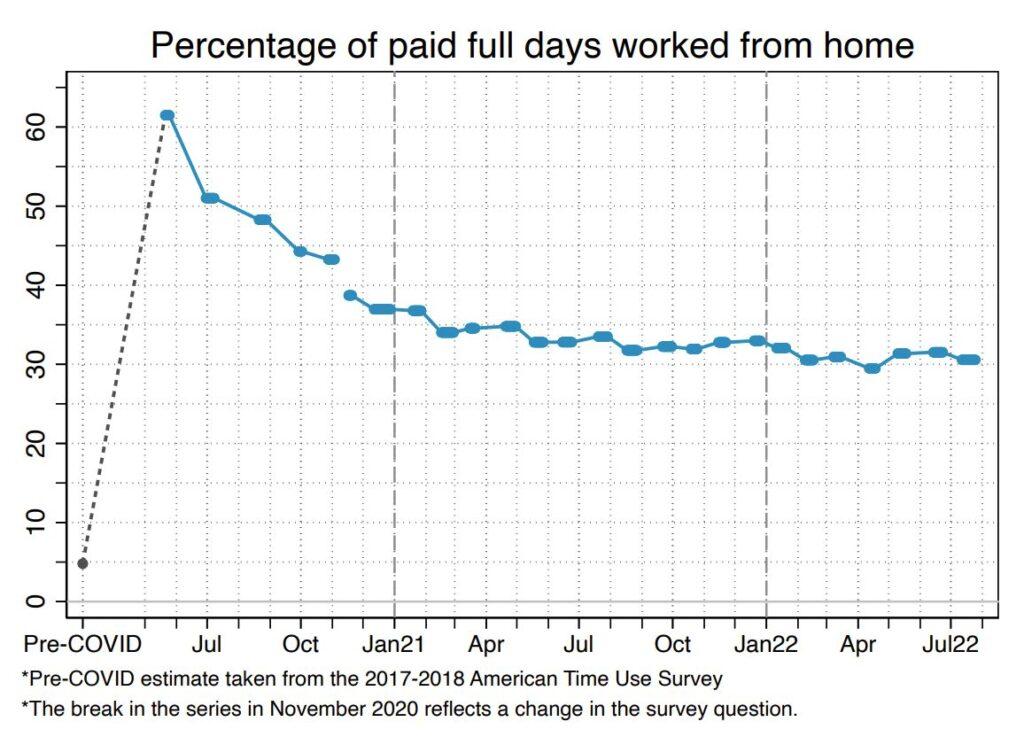

Unlike after recent recessions, the recovery from the COVID-19 recession has not resulted in a surge in growth in large U.S. metro areas. Instead, an even greater number of residents are leaving metro areas than before the pandemic. Postal Service change of address data shows that migration from Northern Virginia has continued unabated through the first half of 2022. Though each recession and expansion is different, the most obvious difference since 2020 is the large increase in remote work, a trend that we noted in January of 2020 was already beginning to influence population growth. The sharp increase in the number of remote workers who can now live much further from their central offices has resulted in a shrinking population near a number of major job centers. The surge in remote work has also has boosted the populations of many attractive and often relatively affordable recreation-focused communities that in the past were primarily vacation destinations.

Well before the pandemic, Virginia was losing population to more affordable, fast-growing southern states, and, with a relatively affluent but slow growing population, was beginning to look demographically and economically more like its northeastern neighbors and less like a Sunbelt state. Since the start of the pandemic and the increase in opportunities for remote work, Northern Virginia has experienced a rise in the number of residents leaving, a trend which could continue. A number of studies have shown that the DC Metro area has one of the largest numbers of workers who could leave and continue working remotely. Yet, even as more people are leaving Northern Virginia, slightly fewer people have left Virginia as a whole since the pandemic began. The Commonwealth’s smaller metros and rural areas are, for now, attracting more people, many likely from Northern Virginia as well as the Northeast. For Virginia, the pandemic and the large-scale shift to remote work has the potential to be the most significant turning point in demographic trends since World War II. In this new world of remote work, will Virginia be able to once again attract more new residents than it loses, as it had done for decades before 2013, or will an even larger number of Virginians leave to work remotely in states that are more affordable?